I recently read a new article by archaeologist Charles Higham and linguist Mark Alves on “The Southeast Asian Prehistoric House: A Correlation between Archaeology and Linguistics.”

One of the things I learned from this article is that we have both archaeological linguistic evidence for houses in early mainland Southeast Asia being built on the ground. I had long been under the assumption that early houses in this region had been built on stilts.

In reading this article, I was reminded of a passage from the fifteenth-century Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái Liệt Truyện 嶺南摭怪列傳 (Arrayed Tales of Collected Oddities from South of the Passes) that states that in antiquity, during the time of the Hồng Bàng Clan (Hồng Bàng thị 鴻龐氏), “houses were built on stilts to avoid being harmed by tigers and wolves” (架木為屋,以避虎狼之害).

I’ve long made the argument that the Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái Liệt Truyện is not about antiquity. Instead, it contains imagined stories about antiquity, and the way those stories were imagined by the Vietnamese literati in the fifteenth century was by seeing the “savage” (man nhân 蠻人) people in their kingdom as living at a lesser level of development, and then imagining that as the past of the Vietnamese.

Here is the full passage in the Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái Liệt Truyện that contains the mention of houses built on stilts:

In the early years of the kingdom, the people had insufficient resources for their daily needs. They used tree bark for clothing (other [texts] say for paper), wove reeds into mats, used rice dregs to make wine, made food from sugar palm and windmill palm, salted animals, fish and shrimp, and made salt from ginger root.

They engaged in slash-and-burn cultivation. The land was used mainly for sticky rice, which was cooked in bamboo tubes. Houses were built on stilts to avoid being harmed by tigers and wolves.

They cut their hair short to make it easier to enter the forests.

When a son was born he was laid on banana leaves. When someone died, they would pound on a mortar so that the neighbors would hear and come to help.

There was not yet any betel nut. When boys and girls got married, they would start with [the offering of] a packet of salt, and then complete the ceremony with the sacrifice of a buffalo or a goat. Sticky rice would be brought into the room where they would both eat it, and then they would have intercourse.

My argument is that this is not historical information about antiquity that was somehow preserved for 1500 or 2000 years. Instead, it is ethnographic information about people in the fifteenth century who were culturally different from the Vietnamese literati, and that this ethnographic information about a people that Vietnamese literati viewed as “primitive” was projected into the Vietnamese past and imagined as the early conditions of the Vietnamese themselves (there are scholarly terms for this phenomenon, like “temporal othering”).

Further, this viewing of people who were different as existing at a more primitive level of development was very common in Chinese writings in the centuries before Vietnamese literati wrote this information.

So, having read the new article by Higham and Alves, and well aware that references to “houses built on stilts” was a trope in Chinese writings to refer to people of other ethnicities as “primitive,” I decided to write a blog post about this topic.

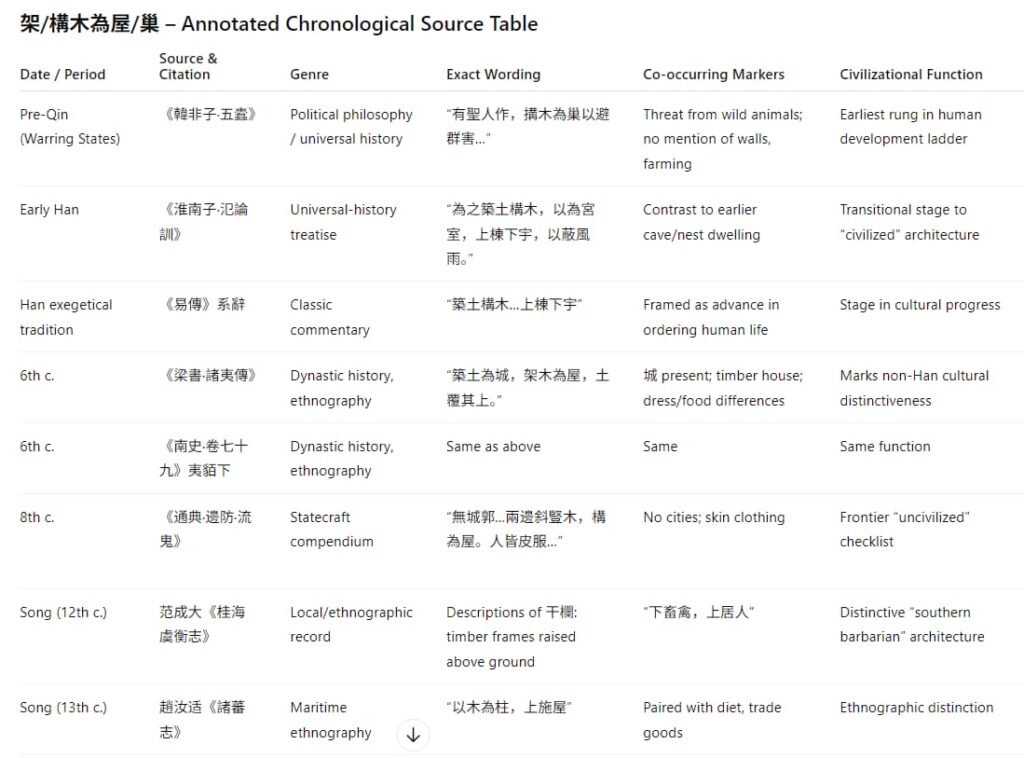

I first went to some of the databases that I’ve used for the past decade or more to look for references to “houses built on stilts” 架木為屋. I found some. But then I logged on to ChatGPT, which today has ChatGPT 5 running, and within two minutes, it had the following blog post written for me.

What ChatGPT found is what I generally knew was out there. It did a better job of writing it up than I could. And it did it in less than two minutes.

Here it is:

Imagining the Past Through the Present: Building Houses on Stilts in the Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái Liệt Truyện

One of the more curious passages in the fifteenth-century Vietnamese text, the Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái Liệt Truyện describes the Hồng Bàng Clan, an ancient people said to have “built houses on stilts to avoid being harmed by tigers and wolves” (架木為屋,以避虎狼之害). Some modern readers have taken this at face value, treating it as a preserved fragment of genuine Vietnamese prehistory.

I don’t think that is the case. Instead, I would argue that this is a piece of historical imagination — one created by Vietnamese literati who projected what they saw around them in the fifteenth century onto their own distant past.

From the Hills to the Deep Past

When we look elsewhere in the same collection, such as the “Tale of the Fox Essence” (狐精傳), we find similar descriptions of contemporary “savages” (man nhân 蠻人) — upland groups living in the hills beyond the lowland administrative centers. They are described as “making houses of wood frames and grass” (架木結草為屋). This is not an archaeological reconstruction of the Vietnamese Bronze Age; it is an ethnographic observation of people the literati saw in their own time, and then imagined about their own past.

The underlying logic was simple: if the “barbarians” living in the hills were less developed than the Confucianized lowlanders, then surely this must be what the lowlanders themselves once looked like. In other words, the past could be imagined by looking sideways at the present.

A Stock Phrase with a Long History

The phrase “build houses on stilts” 架木為屋 was hardly an invention of the fifteenth century. It had a long Chinese textual history, carrying meanings that made it ideal for the literati’s purposes.

From antiquity onward, “build houses on stilts” 架木為屋 or its variant, “construct wood into nests” 構木為巢 appears in two main contexts:

1. As a stage in universal-history narratives – In works like the Han Feizi 韓非子 (五蠹) and Huainanzi 淮南子, “constructing wood into nests/houses” is presented as a practice in one of the earliest stages of human development, before the building of earthen houses or palaces.

2. As an ethnographic marker of “otherness” – In dynastic histories, geographical treatises, and gazetteers, the detail appears alongside other markers of low development: “no walled cities,” “wear skins,” “dig holes for grain.” In such lists, “build houses on stilts” 架木為屋 is not just a building type — it is shorthand for a place lower on the civilizational ladder.

By the fifteenth century, any Vietnamese literatus who wrote “build houses on stilts” 架木為屋 was drawing on this deep reservoir of precedent and connotation.

The pattern is unmistakable: the wording is formulaic, the co-occurring details consistent, and the function — marking a “less developed” stage — stable over many centuries.

Beyond the Trope: What Archaeology Shows

In the Chinese textual tradition, “build houses on stilts” implies a raised wooden structure — often interpreted as primitive, pre-urban, and associated with “barbarian” peoples. But the recent study by Higham & Alves (2025) complicates this picture. [Note: I haven’t gone in to check if ChatGPT got all the names correct here, but the understanding it produces of the article matches mine.]

Combining Proto-Austroasiatic (pAA) lexical reconstructions with excavations across mainland Southeast Asia, they show that in the early Neolithic (5th millennium BP onwards), many houses in what is now Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia were built at ground level. Sites like Rạch Núi, Xóm Rền, Đền Đồi, and Khok Phanom Di have preserved clay, shell, or lime-plastered floors, wattle-and-daub walls, and timber posts — but not necessarily elevated floors. In large Iron Age sites like Non Ban Jak, ground-level houses with multiple rooms, hearths, and even burials beneath floors remained standard for centuries.

Raised structures did exist, especially in flood-prone areas, and the pAA vocabulary (*ɲaːˀ ‘house’*, *ɟə.’raŋ ‘post’*, *kə.’nɔŋ ‘floor timber’*) confirms that posts and floor timbers were part of the building toolkit from the start. But the archaeological record reveals diversity, not uniform elevation.

Conclusion

This means that when the Lĩnh Nam Chích Quái Liệt Truyện presents the Hồng Bàng Clan as living in “houses built on stilts,” it is not preserving a factual memory of early Austroasiatic architecture in the Red River region. Instead, it is applying a civilizational shorthand learned from Chinese texts to a local ethnographic model (upland stilt houses) and projecting that backward into “national origins.”

The result is a constructed past — persuasive to a literate audience because it resonated with both what they could see (the savages 蠻人 of the hills) and what they could read (the Chinese classics) — but out of step with what archaeology now tells us about Neolithic housing.

Again, ChatGPT did that (and more) in less than two minutes.

I didn’t go through and check to see if every reference is exactly right. I checked some, and they were legit. However, to make a truly solid argument, one would have to go through and check everything.

Nonetheless, as an historian, seeing what ChatGPT 5 can do, I’m trying to decide if I should jump for joy. . . or jump off a cliff.